Or: How to Carry On When You’d Rather Dig Your Heels into the Ground and Grind to a Halt

I’ve said this before, but I’m terrible at accepting change. One of the toughest adjustments for me isn’t even that bad. It’s something we all experience on a regular basis. It pales in comparison to traumatic life events like major illness, divorce, job or home loss, war, and death. Many of us probably welcome it, in fact. Yet still, I struggle with it, every year.

You may have guessed what I’m talking about: the seasons. Given my current location in the Northern Hemisphere, I specifically mean the transition from summer to fall. Late-summer days with the crickets chirring and the pleasant-but-not-hot sun warming my face are, to me, the definition of perfection. The natural world feels calm and friendly. I experience moments of certainty that everything is fine, and will continue to be so forever.

Wise people say that perfection is boring. So why is it so hard for me to part ways with the old family summerhouse: the high built-in bookshelves stuffed full of musty tomes, the quaint kitchen ice box, the six generations of family photographs and portraits, the many porches and white-gabled windows, the half-mile-long forested driveway, the view from the bluff of the distant Manitou Islands? Even tougher to leave behind is the land itself: the 200 steps down to the beach, the half mile of wild Lake Michigan waves, the bears, porcupines, and foxes, the 2.5 miles of hiking trails that I poured gallons of sweat into building for hours each day this summer. On my last walk of the trail system the day before our departure, I paused at each of the landmarks I’d named on the trail to say goodbye. That was the saddest end to summer for me.

Left to right from top: Fern Gully, Haunted Birch Grove, Precarious Plunge, Southern Wilds, Streams of Consciousness, Terrace of Triumph, The Monarchy, Vista Sur, Wanderer Track

But the house is not winterized and must sit shuttered and cold throughout fall, winter, and early spring. None of us live remotely close to it, so we can’t visit during those months, either. Not that I would want to – when the nighttime temperature begins to dip into the 40’s, the house starts to feel more like a refrigerator than a home, and it never quite warms up enough during the days. It is a necessary goodbye, and one I understand completely if I stick with the logical side of my brain.

Unfortunately, my brain has a creative, romantic, illogical side as well. It’s this part of me that pats the trunks of the big trees to try to remember the feel of each rough rib of bark. It’s this part that grips the handrails on my last climb up the bluff as if I will never let go. It’s this part that says a silent farewell to all the other bits of myself that have embedded in this summer place as we bump down the dirt drive on our way back to our “real” lives.

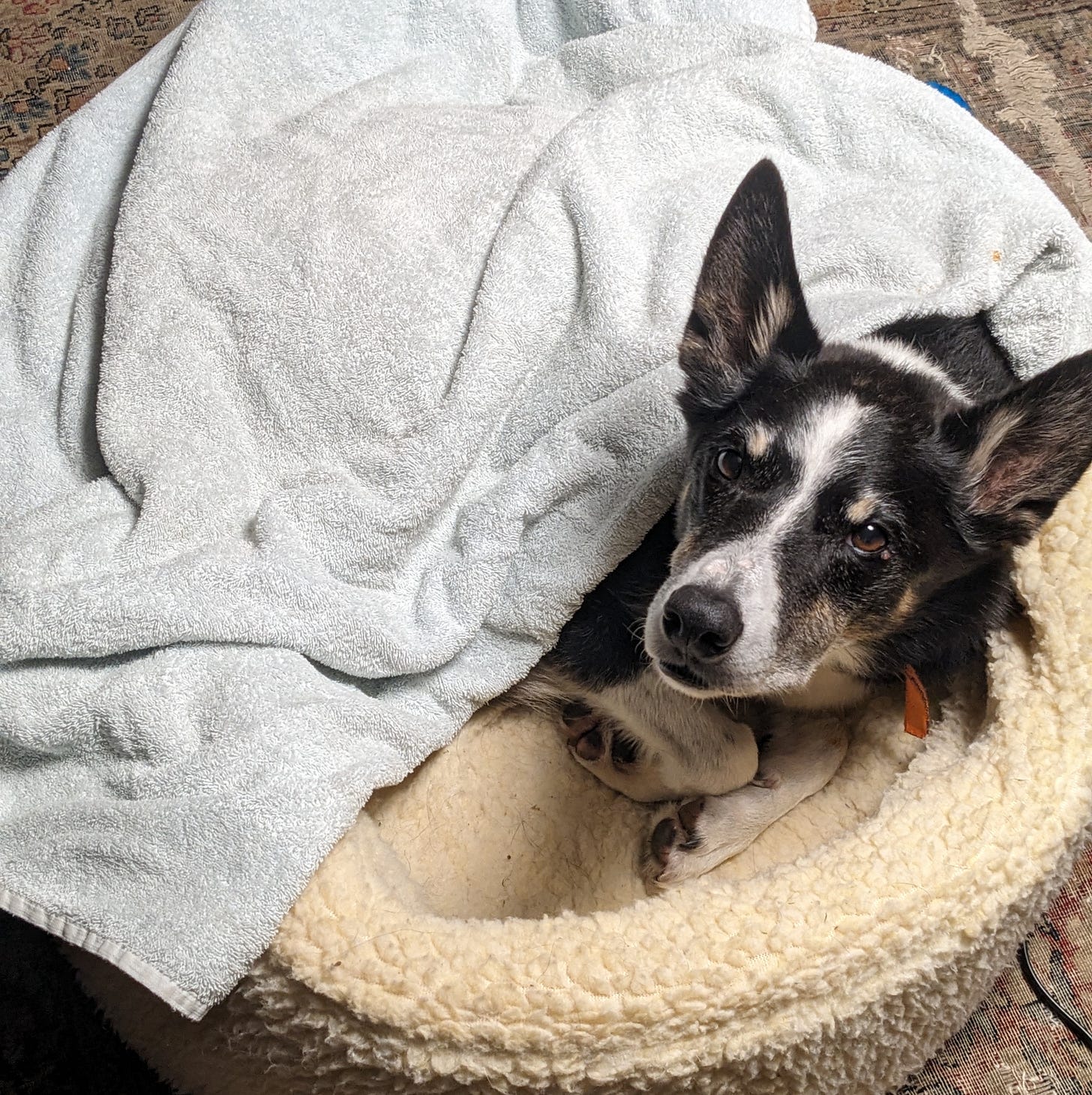

How do I carry on after such a transition? Naturally, I look to my dog. He’s dedicated like no other to the sand, the water, and the trail-building, yet he displays no regrets when it’s time to leave. He simply curls into a ball on the seat and becomes a road-tripping Zombie Dog for as long as it takes to get to his next fun adventure. He’s delighted to return to his other house, his other toys, his other woods and ponds. He doesn’t care that his primary house has little history, that the neighboring woods must be shared with other people and dogs, that his owners don’t spend three-quarters of the day outside anymore. If he could speak, he’d probably reassure me that this is his time to catch up on sleep, to dream of the scents and sounds he stored over the summer (at least, when he’s not reacquainting himself with the scary sheep on the farm next door).

If he can do it, I can, too. During the coming damp, cold winter days, I’ll pull up the pictures of my fifty-nine trail landmarks. I’ll remember what it felt like to tread past them atop the sandy soil, cedar roots, and birch bark. I’ll think of the sound of the waves, the funky smell of the goldenrod, the sight of a fat porcupine waddling over the birch logs that I’d dragged in place to keep the trail out of the mud. I don’t think I’ll ever relish winter the way one might if one has fur and a penchant for snowballs, but my memories of summer will push me along. At some point, those memories will turn into hopes. They’ll pull me toward an enticing future summer that I wouldn’t even know I had to look forward to if I’d never had to leave. I can picture my dog already, rousing himself from his back-seat slumber and pressing his nose to the window when he senses we’re getting close to a change. To something different, interesting, and precious. Always precious.

Maybe if summer weren’t ephemeral, it wouldn’t be so sublime. Those mythical wise people must know what they’re talking about.

Happy Tales!