Do you find your writing sliding into the realm of the subconscious in midsummer? I do, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. The Dog Days of Summer are my favorite time of year.

I get up at dawn just before sunrise, before the heat and the bugs have swamped the woods. There are too many trees to spot Sirius the Dog Star, the phrase’s namesake, but I know it’s there. For one thing, the Romans wouldn’t have put dies caniculares, or “days of the dog star,” in their midsummer calendar if it weren’t reliable. For another, if I were to visit a field in late July or early August on a clear pre-dawn morning with the intent of spotting Sirius, I’m fairly certain I’d succeed (at least until several millenia from now, when the Earth’s wobble will have shifted the dog days to midwinter). Sirius is the brightest star in the constellation Canis Major and the brightest star seen from Earth, after all. The stars of Orion’s Belt—one of the few constellations I can recognize—point southeast, straight towards it.

But the origin of the phrase isn’t why I love this stretch of days.

I think it’s partly because the Dog Days are ushered in by my son’s late-July birthday. For its combination of sheer hard work (labor, right?) and the astonishing and incredible euphoria of holding my baby for the first time, that particular day has imprinted itself in my brain as the best one of my life. It doesn’t hurt that he’s grown into one of the sweetest, most conscientious human beings I know (yep, biased, but pretty close to the truth all the same).

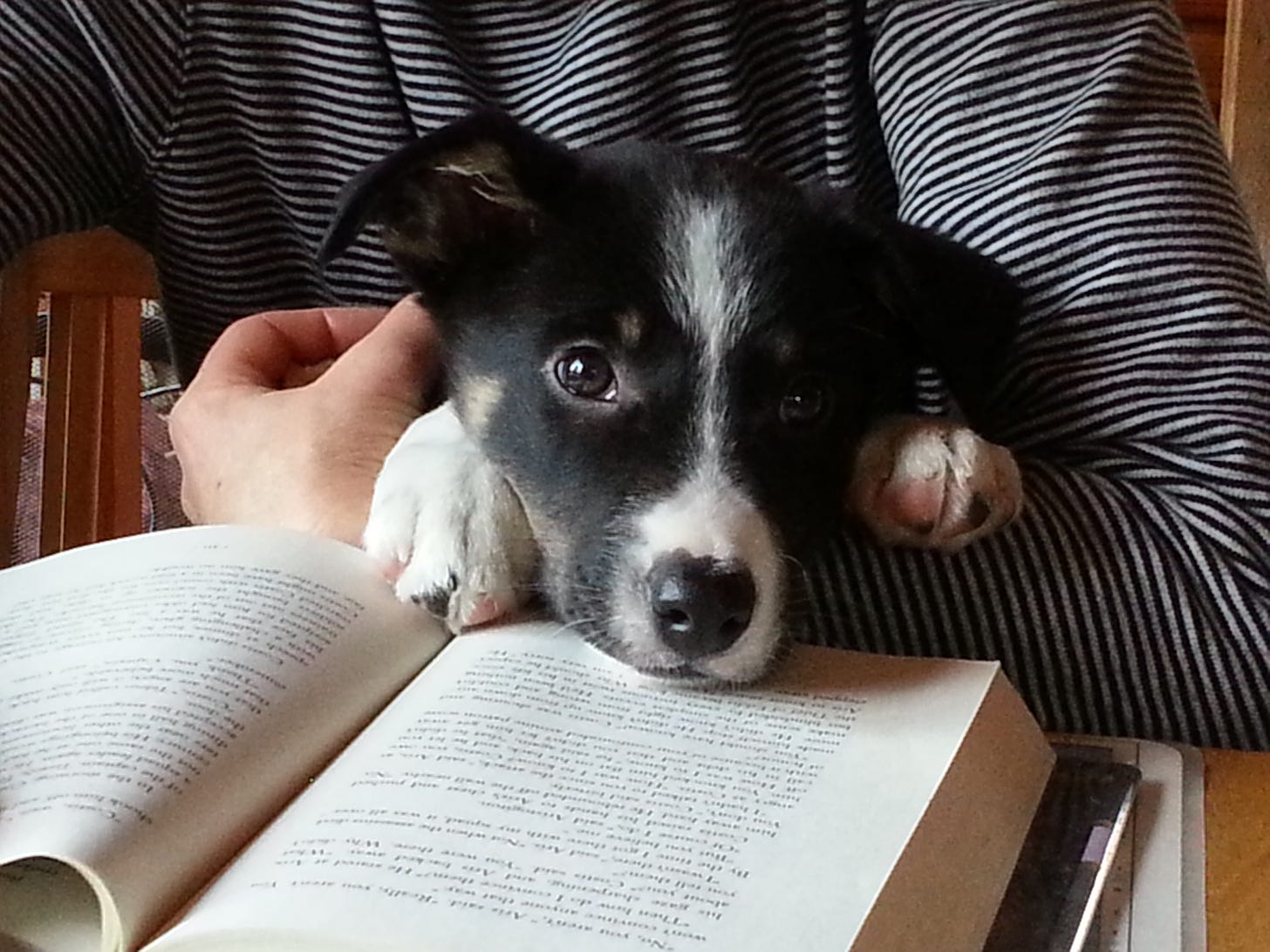

I also love the Dog Days because I’m at last at last down to a single layer of clothing. No more long johns, jackets, or even long-sleeved shirts. The world and I have reached equilibrium. Even as I heat up on a walk, sweat dripping down my cheeks, I feel as if I’m part of everything around me, swallowing and blowing great lungfuls of humid air with abandon, rather than burrowing inside hood, jacket, turtleneck, and gloves to protect myself from the harshness of a winter wind. Through the sultry heat and clouds of bugs, through the great gulps of water my dog and I take from our bottle, through the daily marathons of endurance these walks become, the Dog Days of Summer envelop me in their green, bee-buzzing, frog-burping, osprey-chirping womb.

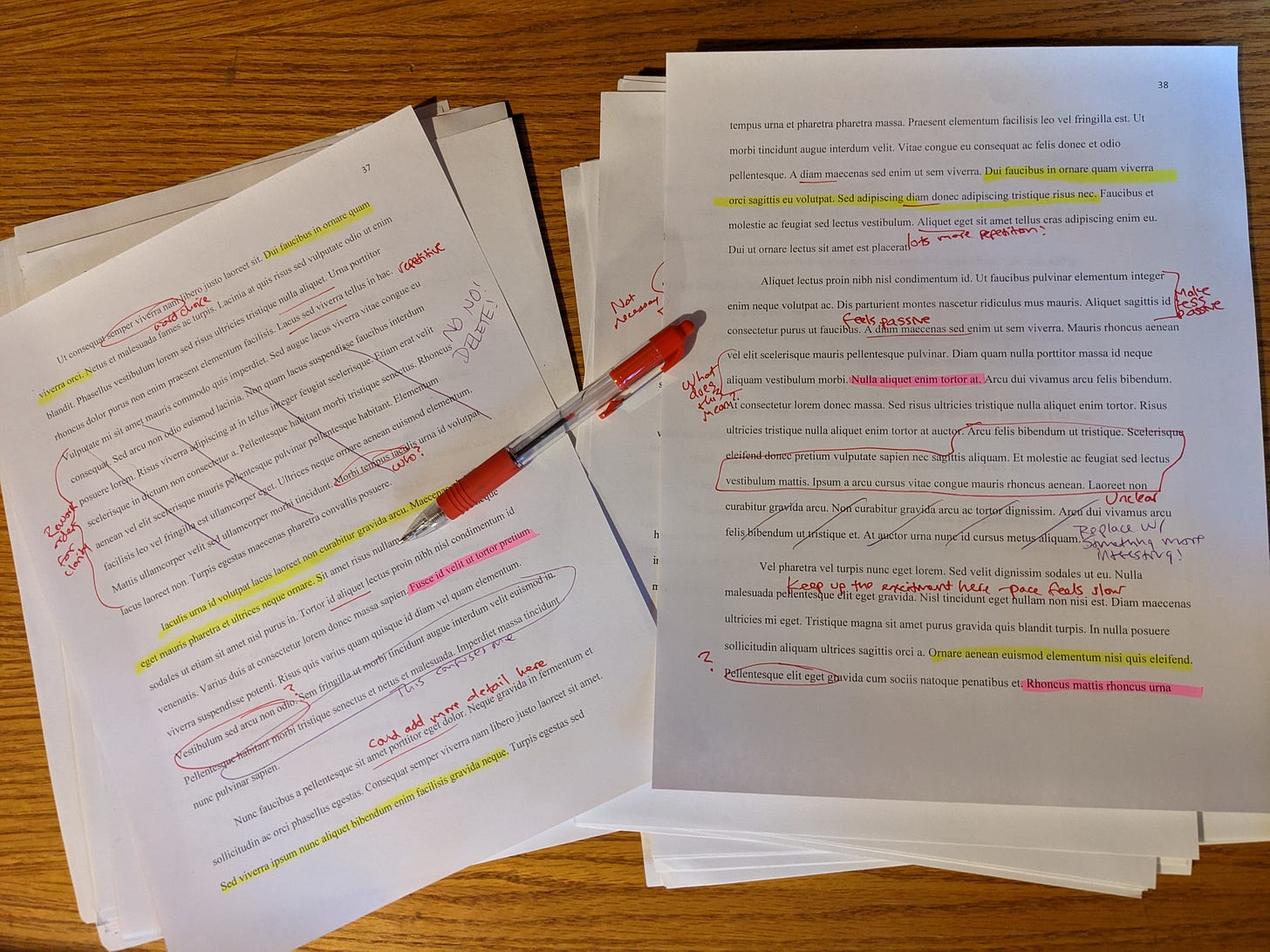

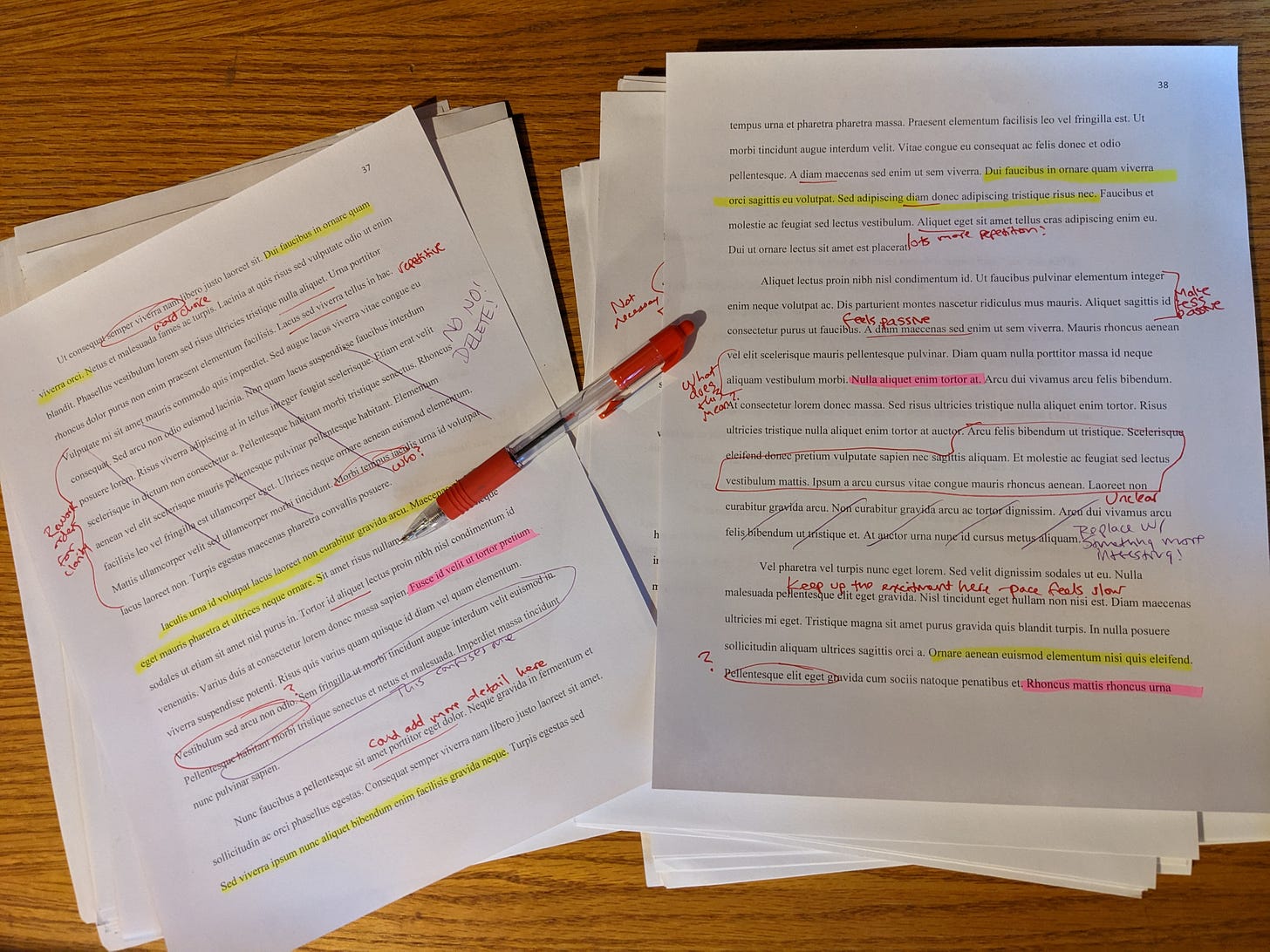

I can’t even picture winter right now. Nor can I imagine myself spending hours each day in front of the computer, wrapped in blankets while exercising my mind. Normally, I jump right into editing a newly completed story, sending the edited version to critique groups, composing drafts of query letter and synopsis, but not during these precious Dog Days. I’m too busy submerging myself in the moment. Each footstep becomes a lifetime of sensations. Any frustrations I felt last month about making progress on my writing disappear. The Earth wraps around me, and I find myself taking the break that everyone tells me should happen after a first draft. My worries slip into the warm waters of the pond along with my dog, into the shovelfuls of dirt in the garden, into the spray of cool water on the azaleas, into the paint on the siding of the house. Hopefully, my subconscious is still working on the story, figuring out how to address the problems that’ll surface when I revisit it. But I can’t be bothered to check at the moment. My conscious mind has detached from it, immersed in the real world. The good thing about this is that after the Dog Days have ended, I’ll view my draft as a first-time reader might. I’ll be able to spot those flaws that my mind glossed over back when it knew the story too well.

But enough of writing. I’m gonna go do some hard physical labor and forget about the state of my draft—and the state of the world, other than its immediate, comforting presence all around.

Happy Tales!