Do you focus afar … or up close?

When I lived in Montana, the “Big Sky” state, I walked in the hills every day. These were grassy rises dotted with Ponderosa Pines, which prefer a lot of open space around their red-black trunks. Mountains rose not only beneath my feet, but miles away, blue with distance. Sometimes the grass was green and speckled with purple lupine, orange paintbrush, and yellow balsam root, sometimes it was brown and shriveled in the summer heat, and sometimes it was covered with a shawl of snow. But no matter the vividness of the hues, no matter the searing heat or the biting cold, my one constant was a sense of space. An expansive feeling, as if I had taken a big breath of helium over the course of an hour and a half walk and could practically float downhill toward home. My dog, too, seemed to feel this way, galloping and leaping far from me for pine cones, rarely slowing in the crisp dry air, even on the hottest of days. We always arrived home tired but exuberant. My head would spin at the thought of the distance we had covered and the far-off allure of hills we had yet to climb. Maybe tomorrow…

To me, this experience of traveling while keeping a loose focus on the horizon mirrors how I feel when I draft a new novel. From that very first step onto the metaphorical path, I have a lofty goal in mind. The top of a hill becomes the “what-if” that my main character is heading toward. What if a musical prodigy suddenly loses her ability to play? What if a phobic kid discovers he has to get rid of his safe space? What if a girl wants to sing, but is forbidden because it’s too distracting? I take some loose warm-up steps and my mind releases the premise, the inciting incident, and the theme. I see the major obstacles my protagonist will face as clearly as spotting a plume of fire on a slope.

As I approach the top, chest heaving, legs burning, I begin to understand how my main character will take a long hard look in the mirror and come to grips with some difficult self truths. I scrabble higher still. The mountain no longer seems impossible to climb. I step to the summit — the climax of the story! On my way back down the hill, the final resolution unfolds. I’m now able to link my characters’ emotional journeys and all of those critical plot developments into a full story. Even the setting becomes more alive. I can see the entire thing! As soon as I get home, my fingers fly across the keyboard as fast as my feet.

Wrong turns happen, of course. Sometimes I end up on a completely different summit than the one I envisioned when I started out. This is not only the reason I spend so much time plotting out a story in advance but the reason it’s so fun. My creativity never feels constricted in any way – not during this plotting stage, nor during the actual writing of the story itself. There’s always room for change.

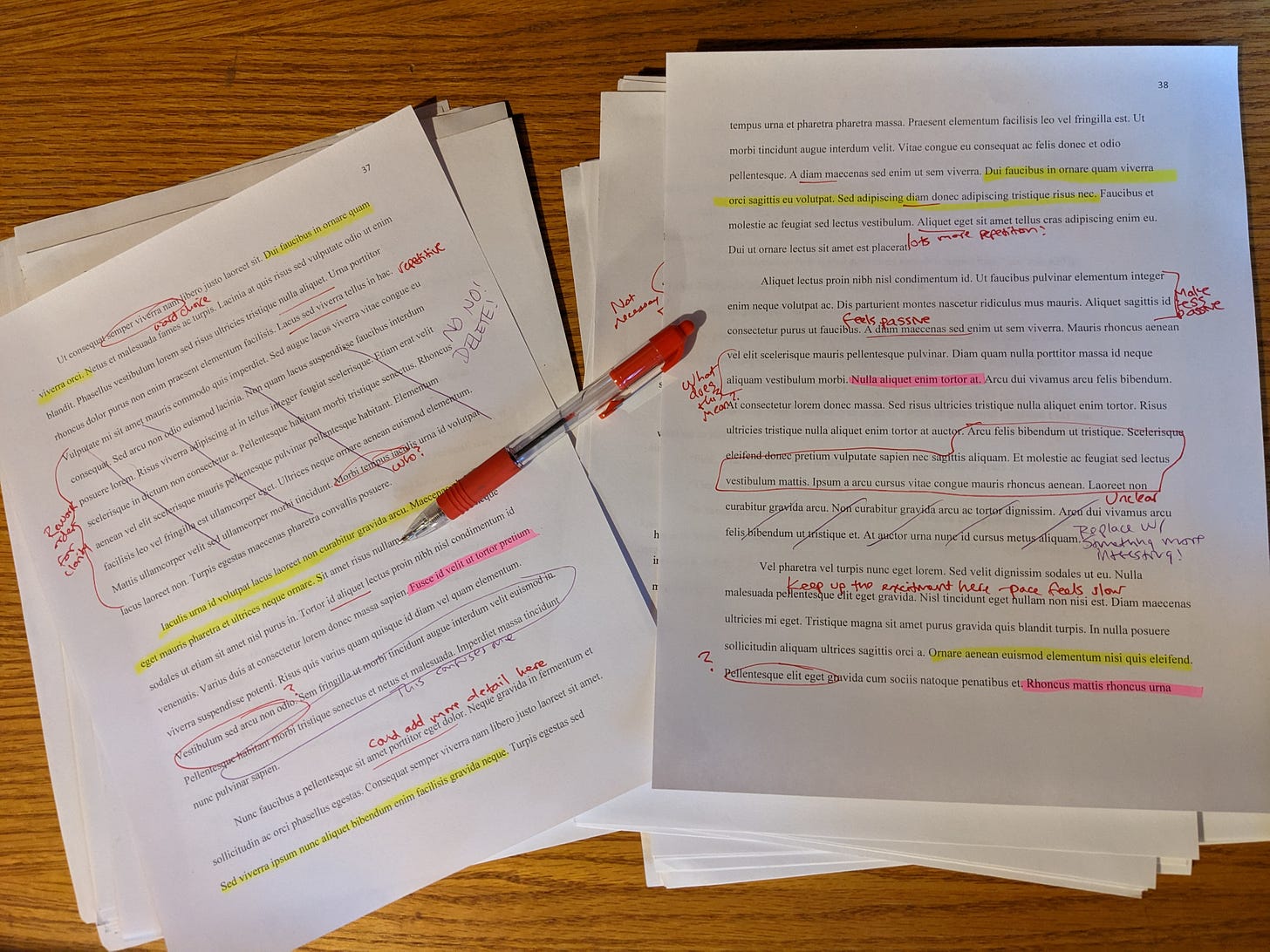

The time for a constricted view comes later in the writing process: the editorial stage. Though revision starts and ends with a big-picture look at the whole story, the majority of the work lies in much smaller sections. It’s crucial to read closely with an eye for detail and an ability to dismantle the writing chapter by chapter, scene by scene, even line by line.

My new daily walks in the woods on Cape Cod are the perfect example of close focus. As soon as my dog and I plunge into the dense vegetation, we lose sight of the sky. We’re immersed in a jungle of branches, vines, and leaves. We follow narrow paths beneath tilted rotten trunks, twisting to avoid the sticky, insect-ridden webs that stretch from one side to the other. My dog bites at deer flies. I swat at mosquitoes.

When vegetation brushes my arms, I think of the tiny, nearly invisible ticks it harbors, carrying all sorts of nasty diseases that can lead to joint pain, fevers, organ failure, and death. Unlike Montana with its bears, mountain lions, and wildfire, the dangers here are so small they can’t be seen with the naked eye: a parasite, a bacteria, a virus. My mind travels inward to dark, anxious problems that I know I must solve. What does my protagonist really want? How can I make her more relatable? Is his voice consistent from one page to the next? Except for a ferry foghorn and a Barred Owl’s hoot, sounds in the woods are small and muffled. A mosquito’s whine, the thud of a foot atop damp leaves. Even the air is difficult to breathe, close, still, thick with humidity.

Such is the slow, painstaking process of revision. If you feel trapped in the minutia of your story, you are not alone.

Yet great beauty lies in the closeness. In some ways, I would argue, it is more vivid and special than those distant spectacular views of mountain peaks. The impossible green of new leaves. The bright pink Lady’s Slipper peeking from beneath a blueberry bush. Mushrooms everywhere, sporting unreal colors on their fruiting bodies. The nutty aroma of dead leaves, so potent in places that my stomach growls, hungry for baked goods. The meandering line of an old stone wall, appearing on one side of the trail and disappearing on the other. The fuzzy face of a young fisher clinging to a tree, seemingly as curious about me as I am about it. The kingfisher skimming the pond’s flat surface, the osprey scanning for fish from its high snag, a chorus of invisible frogs. Something rustling the underbrush: a deer, an otter, a turkey, a gloriously red-brown coyote. I stop to soak in the surrounding jungle with all my senses, my face dripping with sweat or rain. Often I can’t tell which. Though the elevation gain is small compared to climbing an entire mountain, the roller-coaster ups and downs of the trail are just as exhausting. Maybe more so, in the heat of summer.

This slow, strenuous progress is probably why many people dislike revision. But I’ve come to love it. And when I’m finally ready to step back and read the whole manuscript again, to see whether it makes sense, it’s like stepping from the shade of the trees into the sunny field, brushing away the spiderwebs, knowing that soon I’ll wash all the bugs off in the shower, my dog collapsed on his side in a happy stupor. For both of us, only the sense of accomplishment and memories of forest beauty remain.

What’s your favorite part of the writing process: loose focus or close?

How about when you go outside?

Happy Tales!