One of the worst days in many countries occurs with the annual switch from Daylight Savings Time to Standard Time. We have to reset our clocks backwards an hour, and guess what that means? Hint: I’m not thinking that much about you right here. Besides, I know a lot of people relish that extra hour of sleep (excluding myself). No, I’m concerned about your dogs.

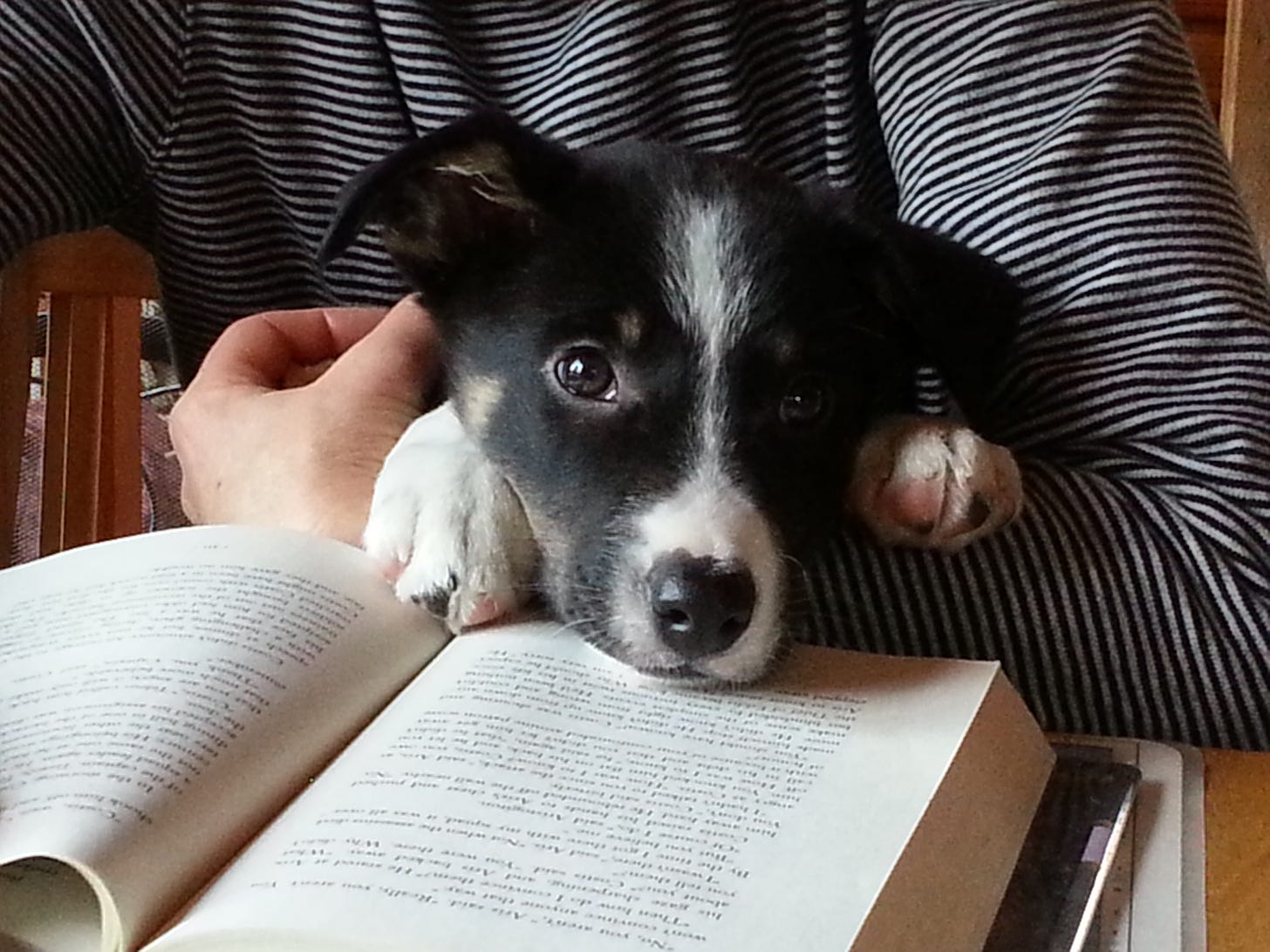

Possibly this goes for other pets, too, but dogs truly love their routines. Delay everything by an hour, and your dog will be standing by your side of the bed, shaking his coat and rattling his tags in anticipation of you getting up (at what is now 4:00 AM rather than 5:00). Then he’ll be standing at your elbow waiting for breakfast—and dinner—an hour before he’s normally fed. As someone who’s perpetually hungry, my stomach growls in sympathy.

And of course, your dog will display signs of restlessness indicating that he expects you to let him out or take him for a walk, long before you’re ready to step outside. At the end of the day, he’ll wonder why you’re taking forever to go to bed. He’s likely to retire early, even though you’re still up and there’s a chance you might play more games with him or even give him a treat.

It takes my dog a good week to get over the time change. For every one of those interminable days, he employs his most beseeching stares for much longer than normal, as though he’s starving to death and suffering tremendously from lack of attention.

My dog’s behavior makes me feel rather callous. But I cold-heartedly push the new routine into place because once he’s adjusted, we’re back to our usual schedule. It’s probably during this process more than at any other time of the year that I appreciate Tock’s intense devotion to the precise moments that good things happen for him. Without a watch or a phone or a daily planner, his brain makes use of other cues to understand timing. This could be external, such as changes in daylength and temperature, or internal, such as his level of hunger, alertness, or sleepiness. Whatever it is, he’s as accurate as the atomic clock in our weather station.

If you’re lucky enough to spend much time outside, you’re likely aware that wild plants and animals have their own clocks, too. Over millennia, each species has evolved in a way that enhances its own survival and ability to pass on its genes to the next generation—and a large part of its success stems from knowing exactly when to flower and fruit, when to eat, migrate, and grow a new coat of fur.

A hummingbird that arrives so early that its crop of flowers isn’t yet producing nectar—or so late that the flowers are already drying up—won’t have as much food to support its young. Likewise, a grizzly bear that comes out of hibernation too early may not find enough of the delectable glacier lily bulbs that it relies on for spring nutrition in many alpine areas.

The problem, unfortunately, is that global changes in weather are now happening at a more rapid pace than ever before, and they’re wreaking havoc with natural systems. Like the white-coated snowshoe hare on a brown, melted-out hillside, some species are unable to adjust their tortoise-slow evolutionary processes to keep up. And unlike my dog, they don’t have the luxury of muscling through a week of misery and just “getting used to it.” Many species do alter their physiological and behavioral patterns in a way that seems to correspond with longer warm seasons, but they’ll be in trouble if the plants they eat or the animals they interact with don’t adjust at precisely the same pace, or if severe weather becomes more unpredictable overall.

“No species lives in isolation,” says professor David Inouye, leader of the world’s longest and most comprehensive study of ecosystem phenology in the southern Rocky Mountains (i.e., an incredible fifty years of measuring the timing of interconnected biological cycles). The big unknown question today is whether the major life events of different species will continue to become more and more mismatched. Perhaps new species will step in to fill the void where others cannot, but the chances of these newcomers meshing perfectly in an already established ecosystem are small. Clearly, we need a lot more research to determine the answer.

At the moment, it feels to me like we’re living inside a massive global climate experiment with no controls and too many study subjects doing whatever they please. It’s my fervent wish that we humans do what we can to slow climate change down, so other species have a chance to adjust their routines in order to survive and reproduce. But how?

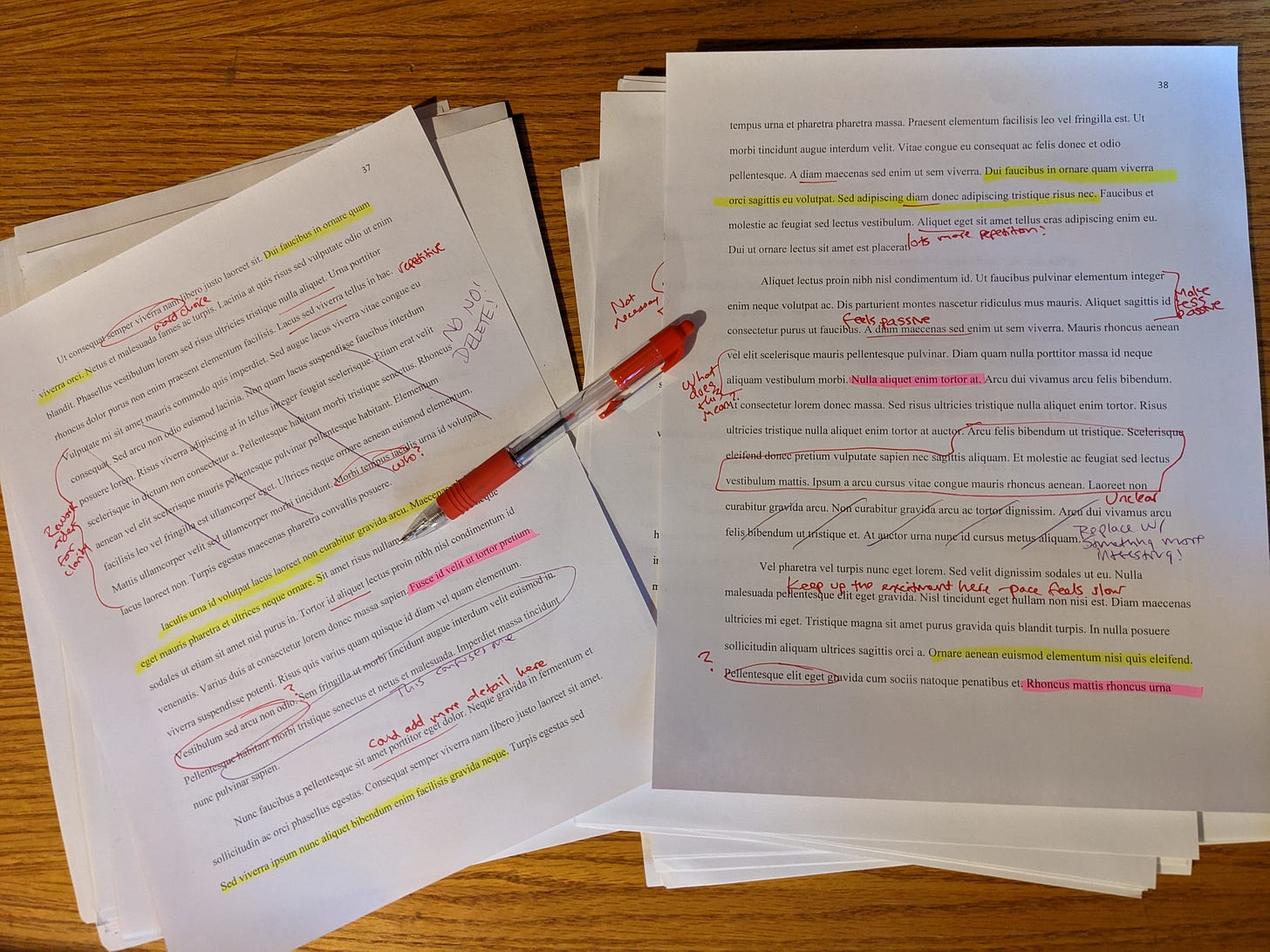

This is when I fall back on the thing that keeps me grounded most of all—writing. It’s one area in which I personally might be able to make a difference, by shedding light on the things that matter to me. Climate change, for instance. Once people appreciate the intricate balance of life forms that comprise an ecosystem, they might begin to think about how easily that can be upset, and how they can minimize their own contributions to climate-related turmoil.

So … I write. And I’ve found that I write best when I stick to a certain schedule. For me, this means a small chunk of time before dawn followed by a larger chunk at mid-day. Of course, the actual frequency and amount of writing time varies with each person. Some write best in the morning, some in the evening, some interspersed throughout the day. The main thing is that we know we have to write, and we dedicate blocks of time to doing it. We have routines. It’s my guess that most successful writers are as embedded in their routines as their dogs. How else would we ever trick ourselves into writing more than a paragraph?

Routines are bread and butter for writers, and we rely on them in order to create. Whether we think about the survival of an entire ecosystem or witness the angst our dog feels during the time change, appreciating the importance of routines ensures that we’ll do what we can to maintain them (or to ease the transition to a new one as gently as possible, in the case of that shift to Standard Time). This gives us the concentrated time we need to let our thoughts flow into words. It’s personal and perhaps selfish, but to me, writing is the real reason for my own routine. Without one, I’d never have written this.

Happy Tales!