My dog does lots of things with confidence. He performs agility obstacles at high speed, he races through the woods and leaps in the air after pinecones, he willingly meets people and most other dogs—especially old border collies, and he’s only a little bit scared of sheep (okay, I know that’s weird for a herding dog). But there’s one thing that fills him with absolute terror. When subjected to this particular thing, he can think only of his need to escape, to the point that I use two leashes hooked to both collar and harness to make sure he can’t make a quick getaway.

What is this awful thing and why would I make my dog endure it? If you’re a dog owner, you might have guessed already.

The vet’s office. Yep, that super friendly place where dogs get treats and the staff is interested in nothing more than Tock’s health and well-being. Lots of dogs dislike going to the vet, but why does my dog go into mental meltdown over it? I’m a dog trainer, for goodness’ sake. How come I can’t seem to train him out of it?

This description I’ve presented of my dog could remain just that—a mystery—if I didn’t fill you in on some crucial details from Tock’s past. In other words, I need to provide one of the crucial backbones of any story to this situation: the use of backstory.

Backstory has a pretty bad reputation in the eyes of editors and critiquers, but not because it’s unnecessary. In fact, it’s an indispensable tool that helps writers flesh out characters and explain character motivations—their desires, hangups, fears, and needs. The problem with backstory isn’t in using it, but in misusing it. Beware, writers, of succumbing to the temptation to give your readers every little detail about your characters’ former lives in the early chapters of your story!

The best backstory doesn’t all happen right away, but in small doses that leave you wanting more. You can drop clues into dialogue, into the way characters react to external situations, and within their thoughts. I love presenting snippets of interiority right before or after my protagonist says or does something that needs further explanation. But again, I keep it as brief as possible to avoid unnecessarily slowing the pace and leaving the reader feeling as though they’ve become mired in a swamp of information.

If Tock were my main character, I might show him trying to slip his leash in front of the vet’s office, followed by him thinking: This is the home of that evil microchip. Must flee before it attacks me again! Then I’d continue on with the early events of the story without dwelling further on Tock’s evasive action until he again does something that requires a little more insight.

Another scene I might write in the early pages to develop my main character is one in which Tock emits a hopeful little whine when he sees an old border collie. The sweetness of this sound would give the reader some early empathy for Tock: a true “Save the Cat” moment, as recommended by writing craft expert Jessica Brody. Tock’s interiority for his action and “dialogue” would read something like: Moth, is that you? Tarzan, I miss you.

So at this point you have enough information to understand why Tock loves old dogs so much—especially ancient border collies. The ghosts of our past pets drift through our thoughts forever, as well as through the minds of other animals in the family who knew and loved them. It’s terribly hard to say goodbye to a departed dog’s story, but one thing that makes losing them easier is seeing their memories and spirit carried on in the next generation. When Tock plays gently with an old dog, I’m reminded of Tock as a puppy, running circles around and beneath Tarzan, while old Tarzan gently waved his big white plume of a tail.

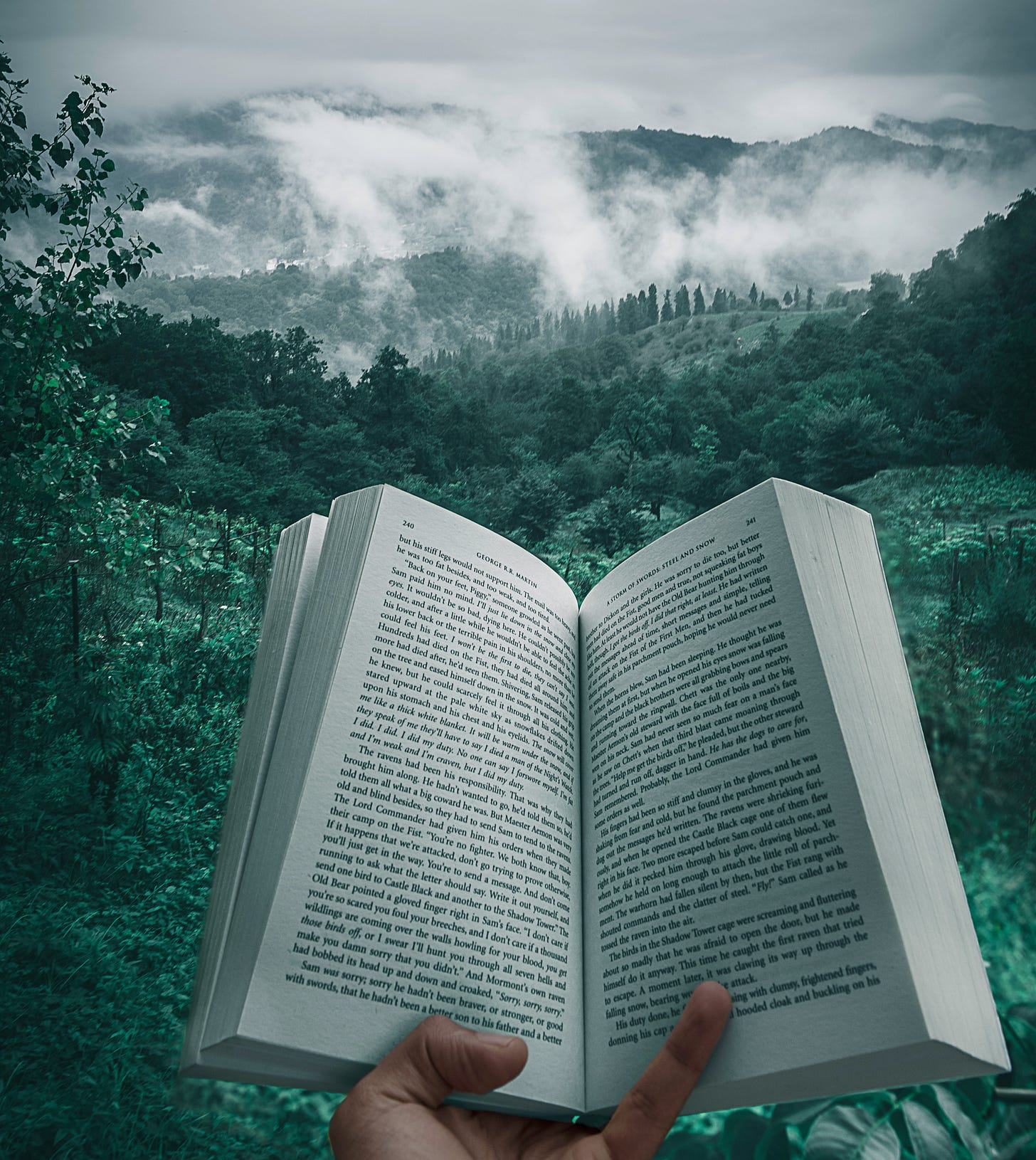

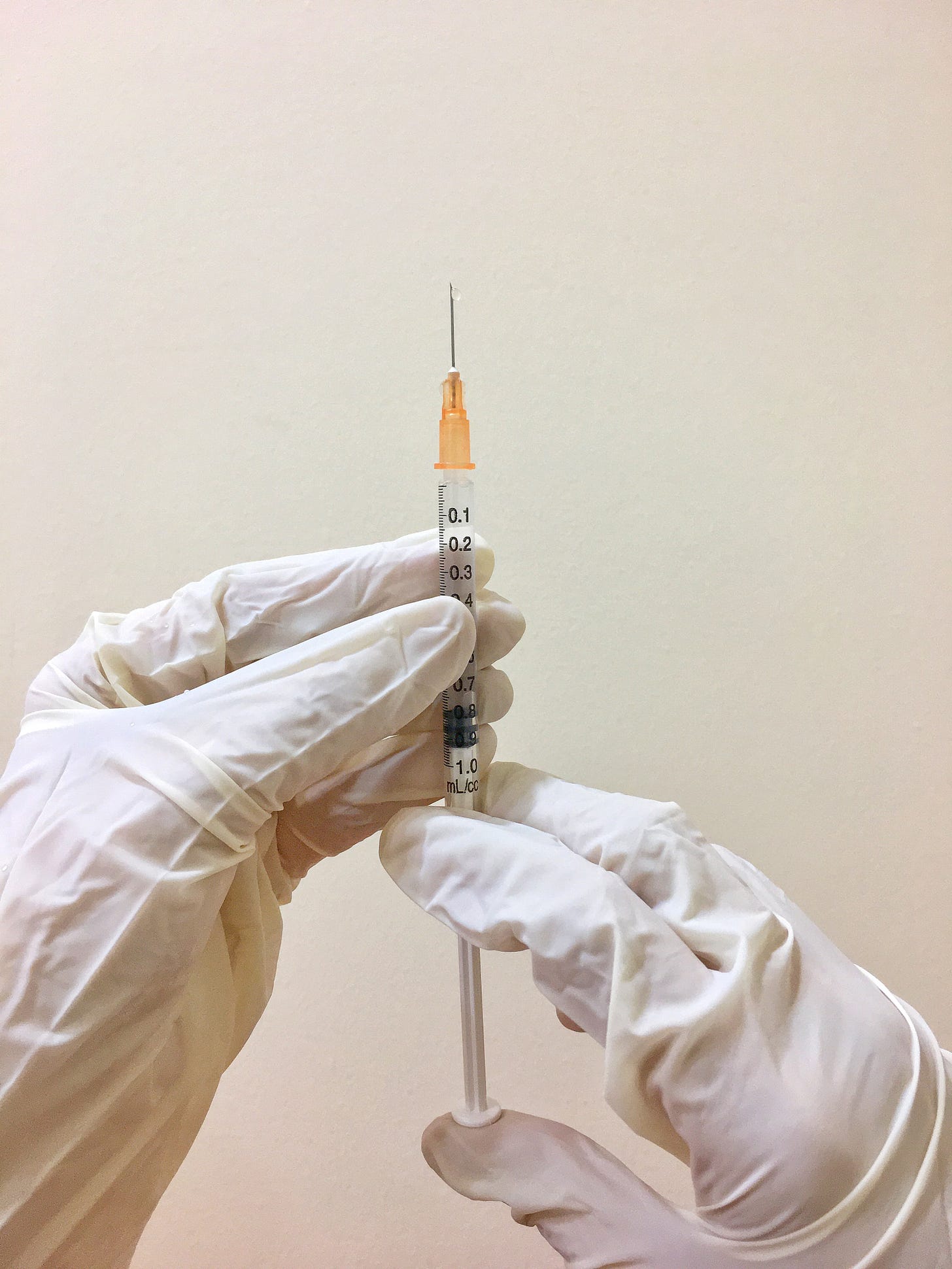

But what about the vet? If I were writing a story of Tock’s life, I’d eventually show him in a scene where he’s especially fearful—perhaps startled by the owl in the picture above, and ideally by something related to the story’s inciting incident. As the scene develops, darker thoughts of Tock’s former fears would begin to surface. Fear of his new owner (me), taking him away from the ranch where he was scared of the sheep. Fear of ravens circling overhead that made him want to run inside, fear of entering a big barn door at his first agility competition, fear of entering a dog crate even though it was exactly the same as his much-loved crate at home. And then the culmination … fear of a big fat needle, plunged into the formerly happy-at-the-vet puppy in order to insert a microchip.

The problem, you see, stemmed from the extremely strong fear periods that Tock exhibited until he was at least two years old. None of my other dogs had them, or had outgrown them by the time I adopted them. I didn’t even fully comprehend what was going on until after the fearful incidents had passed (bad, bad dog owner). But subjecting a dog to that needle when he was in the middle of a fear period made him certain for life that the vet was out to kill him. Gradual reintroductions to the vet “just for fun” all backfired, resulting in him refusing even to get out of the car. At this point, I only take him in, double-leashed, for his annual shots and whisk him out fast, in order to keep his terror to a minimum.

Whew. That little demonstration of backstory is my embarrassing admission for the day. But examining my life as a dog owner gives me a free tutorial in backstory’s value in explaining why characters do—or won’t do—various things (never do something scary with a dog during a fear period!).

Perhaps it can help us learn from our mistakes on a more global scale as well. As a scientist, I know full well the importance of developing one’s hypotheses and experiments based on the research that came before. And as writers, of course, we can’t help but be influenced by the wealth of wonderful stories that have already been written. But there are lots of things we humans could keep expanding our knowledge, some more desperately needed than others. My personal favorites include (list warning!): reducing air and water pollution, supporting alternative energy in order to mitigate climate change, managing natural resources so they can sustain plant and animal biodiversity, and reducing the use of non-biodegradable products. But caring enough about these issues to take even a single step towards their solution requires us to know what’s already happened—both the good and the bad. Like fleshing out a character in a story, revealing the facts of our past—our collective backstory—will help us build a stronger future on this planet we all call home.

Happy Tales!